“Avoid emerging markets when everyone talks about them and invest twice as much as usual when nobody likes them” said Antoine van Agtmael, a World Bank economist who coined the term “emerging markets” in 1981. (It sounded a lot better than “Third World Countries.”)

Yet, contrarians who have bet on emerging equity markets in recent years have been persistently disappointed. The US stock market has been so dominant for so long that, going into 2025, the combined value of its three largest public companies—Apple AAPL, Nvidia NVDA, and Microsoft MSFT—exceeded the entire market value of the Morningstar Emerging Markets Index. It’s not surprising to see funds and exchange-traded funds focused on emerging markets in a state of deep outflows.

Could emerging markets reemerge? In recent months, Chinese equities performed well, while India has been attracting global attention for a while now. I also noticed quite a bit of long-term bullishness toward the asset class in the expert forecasts compiled by my colleague Christine Benz at the start of the year. Most of the surveyed firms expect emerging-markets stocks to outperform US equities over the next 10-15 years.

The time feels right to examine the broad asset class, pondering two questions: Could emerging-markets stocks rise again? And what do they contribute to an investment portfolio? (Future columns will focus on specific emerging markets, including China and India.)

A Period of US Exceptionalism and Emerging-Markets Weakness

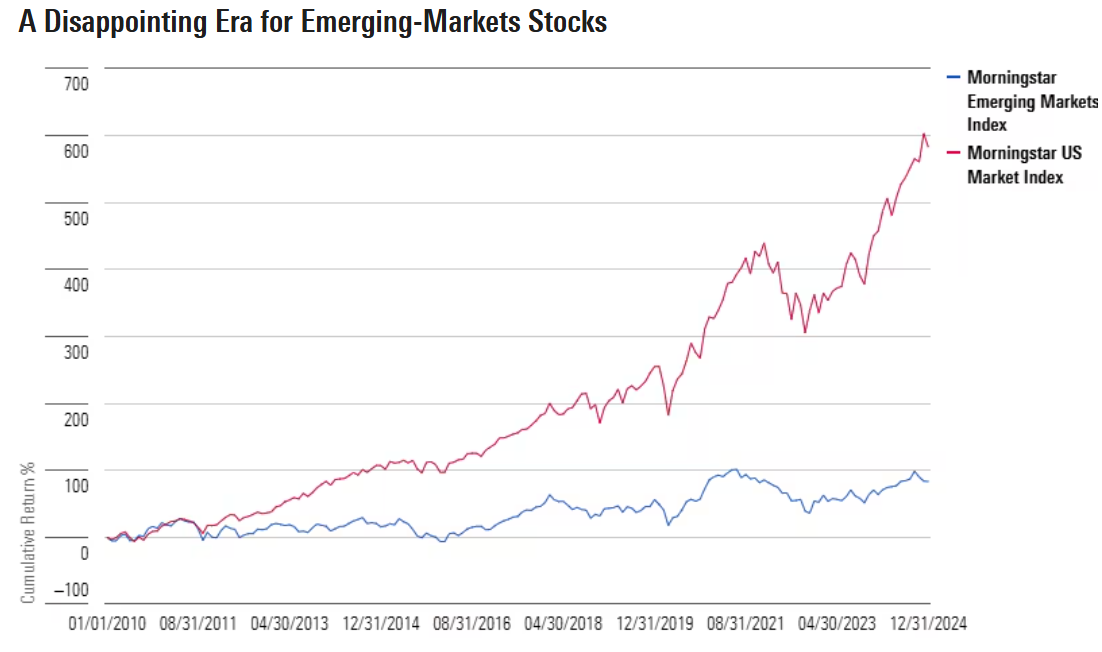

Over the past 15 years, the Morningstar Emerging Markets Index, which includes more than 3,500 stocks, largely from Asia and Latin America, has registered disappointing returns. As displayed below, it gained just 83% in cumulative gross returns from 2010 through 2024, while the Morningstar US Market Index rose nearly sixfold.

The lagging performance is both a story of US exceptionalism and emerging-markets weakness. As we all know, a cohort of phenomenally profitable, fast-growing, technology-oriented American companies has dominated the global investment landscape for more than a decade. US stocks rose from roughly 40% of the Morningstar Global Markets Index‘s value in 2009 to 64% share as of 2024’s end. Meanwhile, the biggest contributor to Morningstar Emerging Markets Index returns has been Taiwan Semiconductor TSMC. It has benefited from many of the same tech trends as its global counterparts, but it’s an outlier.

The US dollar’s strength has been a key part of the story. After bottoming in 2014, its rising value against a basket of global currencies has earned it the moniker “King Dollar.” Currency effects have seriously diminished equity returns from outside the US from the perspective of unhedged US investors. For example, the Morningstar India Index posted an extremely impressive average annual gain of nearly 13.0% in rupee terms from 2010-24, but in dollar terms, that shrinks to just 8.3%.

Other blows that have pummeled emerging-markets stocks include the 2013 “Taper Tantrum,” a collapse in commodity prices, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the political problems of Brazil. China, which will be explored in greater depth in next week’s column, has also detracted from returns. At the end of 2020, Alibaba and Tencent were among the 10 largest public companies globally, and now many investors call China “uninvestable.” It’s a far cry from the first decade of the 2000s when the “rise of the rest” narrative around emerging markets was trending.

Valuations Have Opened Up Opportunity in Emerging-Markets Stocks

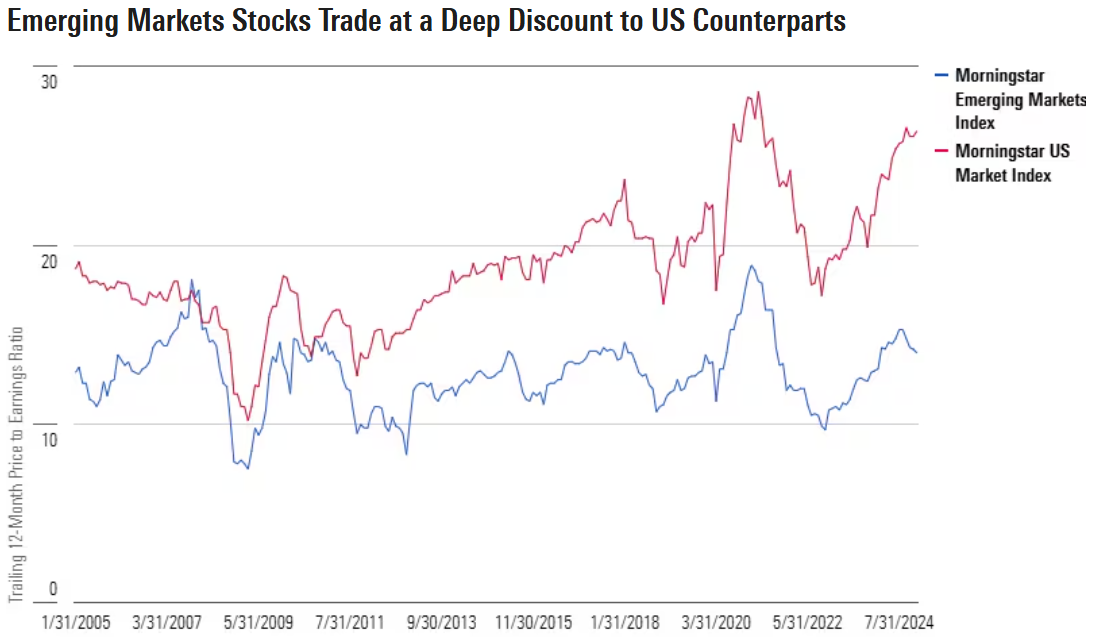

For years now, emerging-markets stocks have traded at a deep valuation discount to their US counterparts. As displayed below, the trailing 12-month price/earnings ratio on the Morningstar Emerging Markets Index was just 14.0 as of the end of 2024, compared with 26.4 for US stocks. We saw an even bigger gap in 2021 when the US traded at twice the multiple of emerging-markets stocks.

Given the current valuation disparity, it’s incredible to think that emerging-markets stocks traded on par with the US in 2010, and, in 2007, at a premium. While the US equity market was experiencing a “Lost Decade” from 2000 to 2009, emerging markets were the hottest asset class around. The “BRICS” acronym caught the popular imagination, and the asset-management industry was happy to oblige with funds focused on the most promising markets of Brazil, Russia, India, and China (and later South Africa). The US Federal Reserve’s move to slash interest rates in 2003 unleashed capital flows, while China’s turbocharged growth fueled a “commodities supercycle.” The European Union’s eastward expansion boosted new entrants like Poland. While the global financial crisis hit emerging markets hard, the asset price rebound of 2009-10, sparked by central banks' aggressive stimulus, put them back on top.

These days, the emerging-markets discount is explained away as a logical byproduct of their risk. Russia’s swift removal from the investment map in 2022 certainly demonstrated that. But I remember the years when “convergence” between emerging and developed markets was discussed as inevitable, and growth potential was invoked to justify rich valuations.

The link between emerging-markets' performance and US interest rates looks to have weakened. The Morningstar Emerging Markets Index outperformed only marginally in 2020 after global central banks responded to the pandemic with rate cuts. And in the bear market of 2022, emerging-markets equities declined in line with their developed counterparts, despite the most aggressive rate hikes in a generation.

Can Emerging-Markets Stocks Outperform Again?

It’s not hard to envision the cycle turning. After all, a long run of US equity market leadership followed a financial crisis that originated in the American economy when sentiment toward the country was bearish. Potential catalysts for emerging-markets leadership could include:

- US dollar weakening or US equities falling short of high expectations

- Earnings growth coming from India, Indonesia, or other markets

- Unloved markets like China, Brazil, and Mexico surprising on the upside

- The clean energy transition, which is benefiting emerging-markets companies, from suppliers of basic materials (like copper) to businesses involved in electric vehicles, batteries, and so on

- Supply chain changes (“Nearshoring,” “Friendshoring,” and so on)

My colleagues on Morningstar’s research and investment-management teams certainly foresee good things from the asset class. Looking at the 10-year return forecasts in Morningstar’s 2025 Outlook, the three global equity markets with the most upside potential in their view are Brazil, China, and Korea: “For long-term-oriented investors, a period of uncertainty can often be a great time to buy, particularly for those who can ride out short-term volatility.”

The Diversification Benefits of Emerging-Markets Stocks

There are also reasons to own emerging-markets stocks for what they contribute to a portfolio. According to Morningstar’s 2024 Diversification Landscape report, emerging-markets equities have been less correlated with the US, and those correlations have actually trended down since 2000. In the words of the report:

“Longer-term correlations also demonstrate that emerging markets generally have a lower correlation with US stocks than developed markets do. That’s because the types of industries that are especially prominent in emerging markets, particularly energy and basic materials, have declined as a percentage of the US market. In addition, the Chinese economy, which represents roughly 30% of major emerging markets indexes, follows a different economic cycle than the US does. Finally, emerging markets are more likely than developed markets to be affected by country- and region-specific geopolitical events—political instability, wars, and currency devaluations—that have little to do with the US. Taken together, those features suggest that emerging-markets equities' low correlation with US stocks won’t be as fleeting as some of the other correlation trends.”

Low correlations between emerging and developed markets are cold comfort when the asset class has been a persistent drag on returns. Yet, market leadership is dynamic, and emerging markets have recovered from downcycles before. To me, the possibility that emerging-markets stocks will reascend makes them worthy of a place in an investment portfolio. My colleague Amy Arnott recommends limiting them to 15% of portfolio assets though.

©2025 Morningstar. All Rights Reserved. The information, data, analyses and opinions contained herein (1) include the proprietary information of Morningstar, (2) may not be copied or redistributed, (3) do not constitute investment advice offered by Morningstar, (4) are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security, and (5) are not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate. Morningstar has not given its consent to be deemed an "expert" under the federal Securities Act of 1933. Except as otherwise required by law, Morningstar is not responsible for any trading decisions, damages or other losses resulting from, or related to, this information, data, analyses or opinions or their use. References to specific securities or other investment options should not be considered an offer (as defined by the Securities and Exchange Act) to purchase or sell that specific investment. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Before making any investment decision, consider if the investment is suitable for you by referencing your own financial position, investment objectives, and risk profile. Always consult with your financial advisor before investing.

Indexes are unmanaged and not available for direct investment.

Morningstar indexes are created and maintained by Morningstar, Inc. Morningstar® is a registered trademark of Morningstar, Inc.